![]() Analyses

Analyses

Loi contre la déforestation : un report est-il nécessaire ?

La Commission européenne vient de proposer de retarder la mise en application de la loi contre la déforestation. Cela ferait suite aux critiques reçues de la part de partenaires commerciaux de l’Europe. Pourtant, d’autres acteurs se sont activement préparés ces derniers mois.

Une loi historique pour la protection des forêts

Les chiffres viennent d’être publiés : en 2023, près de 6,4 millions d’hectares de forêt ont été rasés, soit l’équivalent de 5 fois la surface de l’Île de France. Une superficie encore plus importante -62 millions d’hectares- a été dégradée. 10% de cette déforestation est liée à la consommation de l’Union européenne.

Ces chiffres sont la preuve que les tentatives de réduction volontaire de la déforestation ne fonctionnent pas. Depuis 2014, avec la Déclaration de New York pour les forêts, 140 pays et entreprises se sont engagés à diviser de moitié la déforestation d’ici 2020 et y mettre fin d’ici 2030. Ces objectifs sont très loin d’être atteints.

Cette loi, votée il y a deux ans, est une réponse à l’inefficacité de cette décennie d’engagements volontaires. En cela, elle est historique. Elle doit interdire de mettre sur le marché européen de l’huile de palme, du soja, du cacao, du café, du bois, du bœuf et du caoutchouc s’ils ont causé de la déforestation, de la dégradation des forêts ou des violations de droits humains.

Pourtant, elle est aujourd’hui en danger. Alors, qu’elle doit s’appliquer à partir du 30 décembre prochain, la Commission européenne vient de proposer le report d’un an de sa date d’application.

Un lobby acharné

Ces derniers mois, nous avons assisté à un déferlement d’attaques publiques et de lobby contre ce texte. Cette annonce de la Commission européenne d’un potentiel report de la loi fait suite à une pression sans précédent, exercée par un panel d’acteurs très large.

Ce lobby est avant tout venu de quelques industries liées à la déforestation comme celles du chocolat, de l’huile de palme, du bois, du papier, du café, etc.

Des ministres de pays comme l’Indonésie, la Malaisie ou le Brésil ont bien sûr eux aussi critiqué la loi. Mais l’opposition la plus percutante est venue du sein même de l’Union européenne, et en particulier de l’Autriche.

Le PPE, le parti de la droite européenne, a lui aussi activement œuvré pour cette annonce de report.

Leurs arguments sont divers : certains dénoncent un manque de clarté de la loi qui empêche les entreprises de se préparer, un temps imparti trop court, d’autres s’insurgent d’être concernés alors qu’ils ne représentent pas de risque de déforestation, et d’autres s’opposent globalement aux exigences environnementales.

Pour répondre à ces critiques, la Commission européenne a publié le 2 octobre dernier les éléments de guidance tant attendus… Mais elle a aussi annoncé proposer un report de la date d’application de la loi, initialement prévue pour le 30 décembre 2024.

En faisant ce choix, la Commission européenne a cédé aux lobbies. Elle a décidé d’ignorer les 1,2 millions de citoyens qui ont demandé cette loi, et de pénaliser les entreprises qui ont activement travaillé à la durabilité de leurs chaînes d’approvisionnement ces derniers mois.

Où en sont réellement les entreprises ?

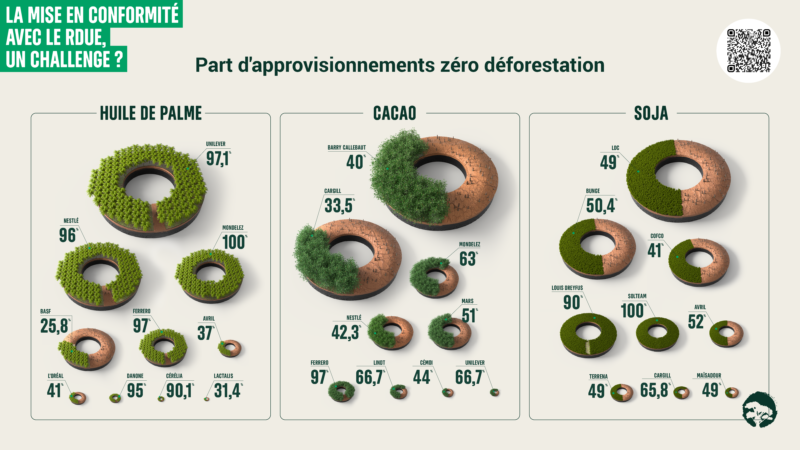

Si quelques entreprises ont traîné des pieds, se cachant derrière le manque de clarté de la loi, de nombreuses autres se sont mises en ordre de marche. Canopée a publié un rapport qui étudie les 22 plus grandes entreprises des filières de l’huile de palme, du cacao et du soja. Celui-ci montre qu’une grande partie d’entre elles sont déjà quasiment prêtes pour l’entrée en application de la loi.

En effet, la filière de l’huile de palme, poussée depuis plus de dix ans par la société civile, atteint déjà des garanties de non-déforestation pour 81% du volume étudié. Ceci est d’abord passé par le recours à des certifications, mais est maintenant complété par un réel travail additionnel de traçabilité et de monitoring de la déforestation. Ce chiffre s’élève à 47,6% dans la filière cacao. Bien qu’il soit plus faible, nous constatons d’importants progrès réalisés ces dernières années. Dans la filière soja, 53,8% du volume étudié serait garanti sans déforestation. Pour cette matière première, nous constatons cependant un important déficit de traçabilité à combler pour se conformer à la loi. Cette filière se caractérise aussi par un manque de transparence, réel frein au travail de traçabilité.

En toute logique, quelques-unes ont clairement pris position contre un report et une réouverture de cette loi. Nous avons organisé un séminaire pour donner la parole à ces entreprises, et le message est clair : « Aujourd’hui, on a de très bons résultats, puisqu’on est presque à 100% de nos approvisionnements garantis sans déforestation » nous explique Floriane Hédé, responsable des approvisionnements et de la traçabilité au sein de Ferrero. « Nous avons besoin d’un autre son de cloche que celui qu’on entend dans les médias. Celui-ci n’est pas cohérent avec tout ce que nous avons mis en place depuis des mois » évoque Raphaël Latz, le Directeur Général de Louis Dreyfus. « Toutes les coopératives avec lesquelles nous travaillons sont déjà en capacité de fournir une traçabilité totale » complète Julien Tisserat, responsable filières au sein d’Ethiquable.

Un large panel d’exemples de bonnes pratiques

Notre étude, en examinant les pratiques de nombreuses entreprises, permet d’identifier les clés pour aller vers des chaînes d’approvisionnement plus durables.

Le premier élément essentiel est la connaissance de sa chaîne d’approvisionnement, à travers un travail de traçabilité. Pour cela, de très nombreux outils existent pour accompagner les entreprises dans ce travail. Ces outils sont déjà largement utilisés par les acteurs les plus avancés, comme SourceMap, PalmTrace, FarmForce, le mécanisme de ZDC, etc. et leur permettent d’identifier les pays, régions, infrastructures, groupements de producteurs, et plantations qui les approvisionnent.

Une fois les parcelles d’origine des produits identifiées, elles peuvent ensuite être contrôlées, afin d’identifier si elles ont été déforestées dans le passé. Là encore, de nombreux outils existent : Satelligence, Global Forest Watch, Starling, Agrosatélite, Earthqualizer sont les plus utilisés. Garantir que ces approvisionnements ne sont pas liés à de la déforestation est donc largement réalisable techniquement. Il ne s’agit que d’une question de volonté.

Enfin, pour faciliter ces démarches de traçabilité et de contrôle, la transparence est un élément primordial. Certaines entreprises, en particulier dans la filière du soja, ont un fonctionnement très opaque et refusent de partager, même à leurs clients, les informations sur l’origine des produits commercialisés. Mais d’autres, en particulier dans la filière de l’huile de palme nous montrent qu’une approche transparente est tout à fait possible. La quasi-totalité des entreprises étudiées qui commercialisent du cacao ou de l’huile de palme ont mis en place un partage des informations de traçabilité non seulement entre maillons de la chaîne d’approvisionnement, mais aussi plus largement : elles rendent publique la liste de leurs fournisseurs.

Des fausses idées disséminées

En plus de la question du manque de préparation des entreprises, deux éléments sont régulièrement avancés pour s’attaquer à la loi. D’abord, elle risquerait d’exclure les petits producteurs des chaînes d’approvisionnement. Si cette question a le mérite d’être posée, au vu de la part que ces acteurs représentent dans certaines filières (85% pour le caoutchouc, 80% pour le café, 70% pour les producteurs de cacao, etc.), il est tout simplement impossible de se passer d’eux. Le travail de traçabilité et de durabilité qu’impose la loi européenne contre la déforestation a cependant un coût, qu’ils pourront difficilement supporter seuls. Plutôt que de brandir la menace de l’exclusion de certains de leurs fournisseurs, les entreprises doivent appuyer ces producteurs, notamment en prenant en charge ces coûts.

Une autre idée reçue est que ce règlement serait un poids pour les agriculteurs européens, à qui l’on imposerait des contraintes supplémentaires, notamment de traçabilité. Ceci est non seulement faux, mais c’est même le contraire : cette loi représente une réelle opportunité pour les éleveurs bovins et producteurs de soja. Leur production n’étant pas associée à un risque de déforestation, ils se retrouveront avec un avantage comparatif face à des importations d’autres pays.

Les conséquences dramatiques d’un report

Si cette loi devait être reportée, cela poserait de nombreux risques. Pour les forêts d’abord. D’après la propre étude de la Commission européenne, ce report d’un an menace directement 230 000 hectares de forêts, soit l’équivalent de 22 fois la surface de Paris. Cela viendrait encore accélérer les émissions de gaz à effets de serre, l’effondrement de la biodiversité et les violations de droits humains associées à cette déforestation.

Mais cela est aussi très grave pour les entreprises qui ont travaillé activement ces dernières années pour se mettre en conformité avec la loi. Celles-ci ont souvent été plus discrètes, et ont moins pris position sur la loi, concentrant leurs efforts sur l’obtention de garanties de non-déforestation et de traçabilité. Plutôt que d’encourager leurs bonnes pratiques, l’Union européenne les pénaliserait directement en actant ce report. Elle enverrait un message clair : il est plus rentable d’investir dans des efforts de lobby que de durabilité.

Revenir sur la loi contre la déforestation, alors qu’elle est déjà votée depuis deux ans, porte également atteinte à la confiance politique dans l’UE. Cette loi est l’un des acquis majeurs du Pacte vert pour l’Europe, et elle a été largement plébiscitée les citoyens. La remettre en cause est un très mauvais signal.

Pire : pour voter ce report, un nouveau processus législatif doit être enclenché, et avec lui, la possibilité d’amender le texte. Ce n’est donc pas seulement la date d’application qui pourrait changer, mais l’ensemble de la loi qui pourrait être modifié. Le texte doit maintenant passer dans les mains du Conseil de l’Union européenne -les Etats membres-, et du Parlement européen. Du côté du Conseil, la prochaine réunion se tiendra le 23 octobre. C’est à ce moment-là que pourrait se décider la position des Etats membres. Du côté du Parlement, une procédure accélérée vient d’être actée. Le texte devrait donc uniquement être voté en séance plénière, par l’ensemble des députés. Cependant cela pourrait ne pas arriver avant le mois de novembre, ce qui laisserait malgré tout le temps de déposer des amendements… Tout va donc maintenant dépendre des députés.

Canopée reste plus que jamais mobilisée pour préserver l’ambition et le calendrier de la cette loi. Nous demandons en particulier au gouvernement et aux députés européens français de maintenir la position de leader que la France a occupée au moment des négociations de ce texte.